Chapter Four: Synthesis

14. A Digital Synthesis Language Sampler | Page 15

ChucK: A Strongly-Timed Music Programming Language

Prepared by Ge Wang

Associate Professor, Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA), Stanford University

A relative newcomer to the computer music programming language scene, ChucK is an open-source text-based programming language for real-time audio synthesis and analysis. It can be downloaded for free from here. Its defining features are:

- a sample-precise unified timing mechanism for multi-rate event and control processing; this effectively removes the fixed distinction between audio and control rate traditionally found in languages such as CSound, Max/MSP, and SuperCollider,

- a simple but powerful concurrent programming model based on time--allowing for audio programs to be expressed precisely and in parallel, and

- a live coding environment (and way of thinking) that supports rapid experimentation.

ChucK was designed for researchers, educators, and artists working with computer-based audio, and has been used in a variety of contexts including computer music classrooms, laptop orchestras, instrument design, audiovisual design, virtual reality design, installation works, generative music systems, and many more. The Made in ChucK section below highlights a few works made using ChucK, offering a glimpse at the diversity of uses of the language.

History

ChucK was created in the early 2000s at Princeton University by Ge Wang and Perry R. Cook, while Ge was a Ph.D. student advised by Perry in the Computer Science Department. The first version of ChucK was released under a GPL license in 2003. Over the years, many researchers, teachers, and artists have contributed to ChucK's evolution. Spencer Salazar created miniAudicle, a GUI-based integrated development environment for ChucK in 2004. The Princeton Laptop Orchestra (PLOrk), created by Dan Trueman and Perry Cook in 2005, began using ChucK for teaching as well as instrument and sound design. In 2006, Rebecca Fiebrink and Ge Wang created ChucK's audio analysis framework, expressed through unit analyzers–the analysis counterpart to unit generators.

Ge join the faculty at Stanford University's CCRMA in 2007, and ChucK research and development became distributed, with developers at Princeton, Stanford, and elsewhere. The Stanford Laptop Orchestra (SLOrk) was founded in 2008 at CCRMA, where ChucK continued to be a tool for instrument design and teaching. In that same year, the mobile music startup Smule was co-founded, which used ChucK on the iPhone as a real-time audio engine for its early apps: Ocarina, Sonic Lighter, Zephyr, and Leaf Trombone: World Stage. Meanwhile, ChucK continued to find its way into computer music curricula, including at Stanford, Princeton, CalArts. In 2015, the book Programming for Musicians and Digital Artists: Creating music with ChucK was published, authored by Ajay Kapur, Perry Cook, Spencer Salazar, and Ge Wang.

Around the same time, Kadenze introduced the online course Introduction to Real-Time Audio Programming in ChucK. Jack Atherton created Chunity, which enables one to program ChucK inside the Unity game development framework. Romain Michon and Ge Wang integrated FAUST and ChucK to create FaucK. More recently, ChucK now runs natively in web browsers (WebChucK). The design of ChucK has been extensively documented, most recently in a 2015 Computer Music Journal article and in the 2018 photo comic book, Artful Design: Technology in Search of the Sublime (see excerpt on ChucK).

Features

ChucK both descends and departs from the lineage of MUSIC-N languages. Like Music-N languages, ChucK adopts the unit generator (UGen) paradigm as a fundamental building block for audio synthesis. Unlike most other MUSIC-N languages, ChucK presents a different mechanism for controlling unit generators over time, using a time-based mechanic and concurrent programming model. We detail these two aspects below.

Precise Control over Time

The following short ChucK program illustrates the basics of 1) how to connect unit generators and 2) how to control the unit generators over time:

// audio synthesis network

// a sine wave oscillator (foo)

//connected to the audio output (dac)

SinOsc foo => dac;

// an infinite time loop

while( true )

{

// generate a random number between 30 and 1000;

// set this number to be foo's frequency

Math.random2f(30,1000) => foo.freq;

// advance chuck time by precisely 100 milliseconds

// this mechanism implies the control rate

100::ms => now;

}In ChucK, the programmer explicitly advances time through manipulating the now keyword (ChucK's notion of the present moment). They can do so by any duration–from that of a single digital sample (1::samp => now;) to milliseconds, seconds, minutes, hours, days, and even longer. In the program above, for example, one could replace 100::ms => now by 5::ms => now or even 2::week => now to control how often a new random frequency is asserted. This control over timing is precise and deterministic. The programmer can make the assumption that they are coding in a kind of “suspended animation." In other words, ChucK time does not advance until explicitly instructed, and any code sequence between time-altering instructions can be deterministically mapped to a particular point on a logical ChucK timeline. This provides a framework to reason about time, and naturally establishes a strong temporal ordering of when code executes.

Time-based Concurrent Programming

Concurrent programming is the ability to write code sequences that logically run in parallel. This is a core feature of ChucK, and extends the time control mechanic from one process to potentially many concurrent processes.

While ChucK’s timing mechanic serializes operations, the concurrent programming model parallelizes code sequences. Concurrency in ChucK operates from the timing information that the programmer already supplies (through the time mechanic described in the previous section), which ChucK then uses to precisely interleave computation across parallel code sequences running within the ChucK virtual machine. This design employs a form of nonpreemptive concurrent programming, whereby programmers have to explicitly yield the current process. However, ChucK programmers effectively already do this when they explicitly advance time and these operations contain the necessary information to automatically schedule concurrency code (e.g., when to yield, when to wake up). This concurrency model requires no additional synchronization in code. Furthermore, concurrency in ChucK inherits the sample-precise determinism that is a feature of the timing mechanism. This deterministic concurrency allows systems with complex timing interactions to be broken down into synchronous building blocks.

In ChucK, a concurrent code sequence is called a shred. Shreds can be spawned in code using a special spork ∼ operation (sporking operates on functions, which serves as entry points and bodies of code for the shreds). A shred, much like a thread, is an independent, lightweight process, which operates concurrently and can share data and synchronize with other shreds. But unlike conventional threads, whose execution is interleaved in a nondeterministic manner by a preemptive scheduler, a shred is a deterministic piece of computation that has sample-accurate control over audio timing, and is naturally synchronized with all other shreds via the shared timing mechanism as well as synchronization constructs called events.

ChucK shreds are programmed in much the same spirit as traditional threads, with the exception of a few differences:- A ChucK shred cannot be preempted by another shred. This not only enables a single shred to be locally deterministic, but also an entire set of shreds to be globally deterministic in their timing and order of execution.

- A ChucK shred must voluntarily relinquish the processor for other shreds to run. In this, shreds are like nonpreemptive threads. When a shred advances time or waits for an event, it relinquishes the processor, and gets “shreduled” by the “shreduler” to resume at a future logical time. A consequence of this approach is that shreds can be naturally synchronized to each other using time, without traditional synchronization primitives.

- Technical note: ChucK shreds are implemented as user-level primitives, and the ChucK virtual machine runs entirely in user space. User-level parallelism can offer performance benefits over kernel threads, allowing even fine-grain processes to achieve good performance if the cost of creation and managing parallelism is low. Indeed, ChucK shreds are lightweight—each contains only minimal state. The cost of context switching between ChucK shreds is also low, since no kernel interaction is required.

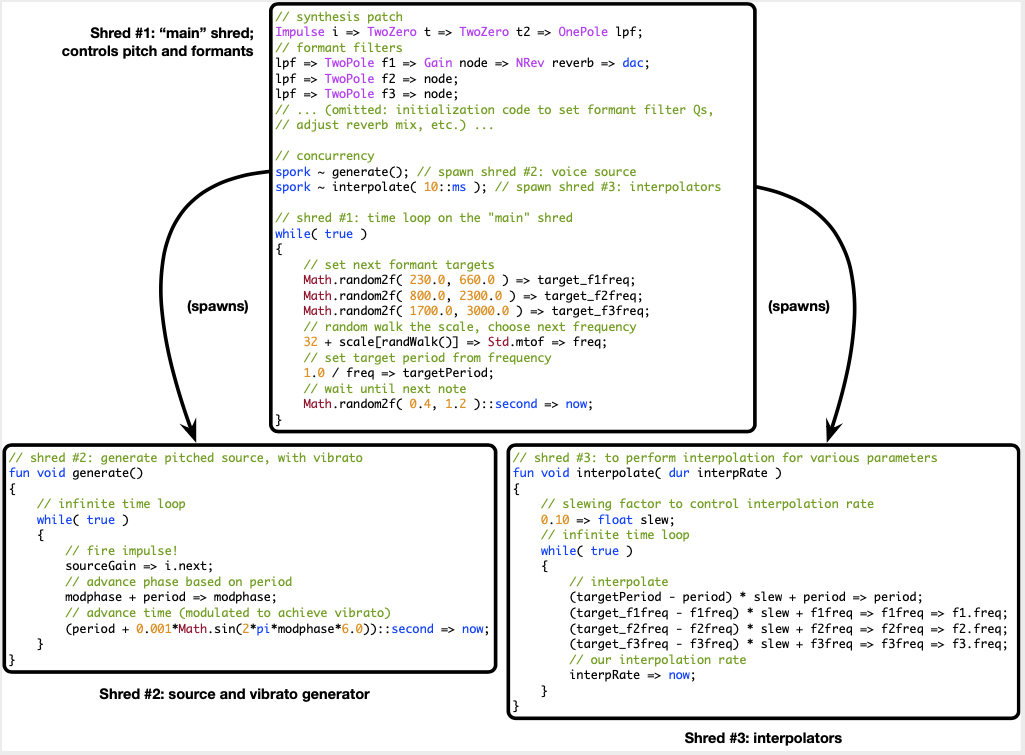

To demonstrate how time-based concurrency works in ChucK, this following example implements a classic source-filter model for rudimentary singing synthesis: an impulse train (the "source", crudely modeling opening/closing of the glottis in the vocal tract) going through a bank of three formant filters (roughly modeling the filtering by the vocal cavity to induce the perception of different vowels). This example demonstrates an elegant way to distribute the task into three concurrent shreds, each operating precisely at their respective and optimal rates:

- a main shred selects the next target pitch and formants.

- doImpulse() generates the impulse train; using ChucK's time mechanic to modulate the impulse train period to create vibrato.

- doInterpolation() interpolates the period and formants, to smoothly glide from note to note, and vowel to vowel.

For brevity, the code pictured below omits some of the setup. The full runnable ChucK program can be downloaded here.

A Note on Control Rates

The manner with which a shred advances its way through time can be naturally interpreted as a kind of control rate (i.e., for asserting control over audio synthesis). Because the amount of time to advance at each point is determined by the programmer, the control rate can be as rapid (e.g., approaching or same as the sample rate) and variable (e.g., milliseconds, minutes, days, or even weeks) as desired for the task at hand. Additionally, the control rate can vary dynamically with time, because the programmer can compute or look up the value of each time increment. Finally, ChucK’s concurrency model allows for multiple, independent control flows to compute in parallel, each with their own programmable temporal profiles.

Made in ChucK

To date, ChucK has been used in an estimated 500 laptop orchestra instruments and works as part of the Princeton Laptop Orchestra, the Stanford Laptop Orchestra , and The Machine Orchestra. A few selected SLOrk pieces, each of which use ChucK, can be found here–include Twilight (2013), Breeze in C (2018), Resilience (2019).

Fun fact: ChucK, running on the iPhone, powered the 2008 Ocarina app, which has been downloaded more than 10 million times. Find out more from the Ocarina full excerpt from Artful Design: Technology in Search of the Sublime.

In addition to various computer music and compositional algorithms courses, ChucK has been used to teach audiovisual design and artful VR design, specifically through Chunity. Here are some final projects, made with Chunity, from Stanford University's Music 256a / CS 476a "Music, Computing, Design" course. In the Stanford VR Design Lab, Chunity has been used to create works including MIDI.CITI by Ph.D. student Kunwoo Kim (also see embedded video below) and Jack Atherton's 12 Sentiments in VR.

To find out more about Chunity, check out the Chunity homepage, Chunity in the Unity Asset Store, and a 2018 paper on Chunity.

In 2022, ChucK was extensively used to craft the instruments and sounds in the first-ever "laptopera" (a laptop orchestra opera) in The Furies: A Laptopera, created by Anne Hege and premiered by the Stanford Laptop Orchestra.

These are a small sampling of what people have created using ChucK. One more, for fun: recreating the THX Deep Note in ChucK.

To further understand the ChucK programming language, one is encouraged to explore the many ChucK examples, the ChucK language documentation, the ChucK book, and the online course. To learn more about the design philosophy underlying ChucK and the design of expressive, playful technology, check out Artful Design: Technology in Search of the Sublime.

Resources

ChucK homepage (Stanford):

ChucK homepage 2 (mirror site at Princeton)

ChucK documentation:

ChucK examples

Chunity (ChucK in Unity):

Unit Analyzers (audio analysis in ChucK):

FaucK (FAUST in ChucK):

2015 Computer Music Journal article on ChucK

Excerpt on ChucK from Artful Design

Programming for Musicians and Digital Artists: Creating music with ChucK (a book on ChucK)

Kadenze Course on Learning ChucK